“Psychoanalysis is about what stops good things coming easily…”

— Adam Phillips, The Beast in the Nursery

What is psychoanalysis?

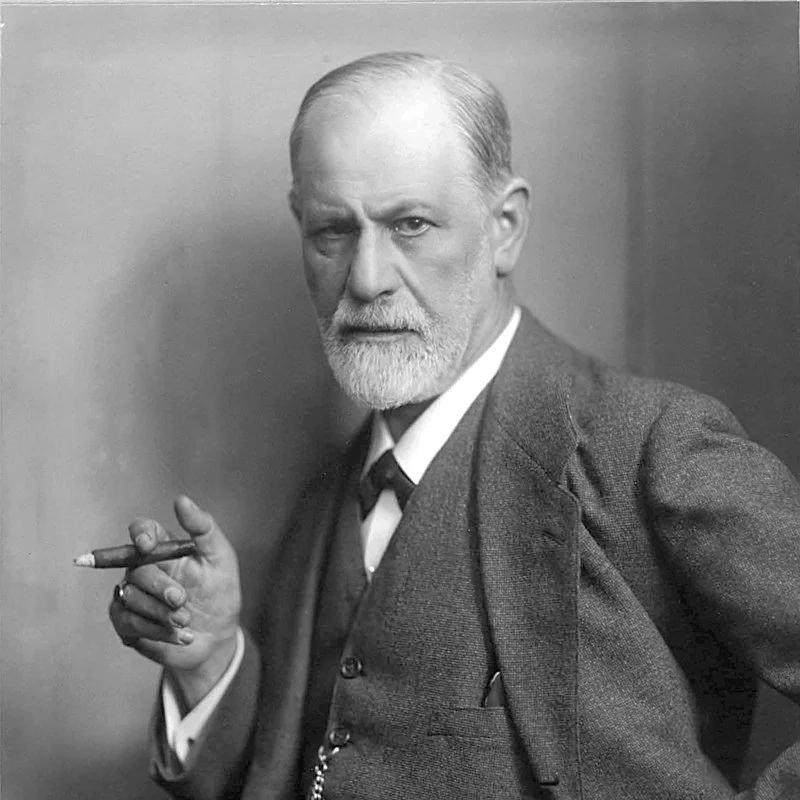

Psychoanalysis is a clinical approach to psychic suffering that builds upon the revolutionary insights and methods of Sigmund Freud (1856-1939). It is distinguished from today’s dominant modes of psychology and ‘talk therapy’ by its preoccupation with the powerful and enigmatic role of the unconscious in our lives, and by its emphasis on the transformative power of speaking freely.

At the heart of psychoanalytic practice is what Freud called its ‘fundamental rule’: that the analysand (or patient) attempt to say whatever comes to mind, no matter how offensive, disturbing, unacceptable, irrelevant, unimportant, or even nonsensical it seems. Over time, this practice—which is seldom as easy as it may sound—can lead to an extraordinarily wide-ranging exploration of our thoughts, beliefs, desires, and personal history, much of which may have been unclear or even hidden from us at the outset. Both the difficulty of ‘free association’ and its often surprising results are evidence of the degree to which our thinking and our behaviour are generally constrained by social norms and expectations.

Psychoanalytic work thus involves assaying what we push to the margins of our lives and our minds, along with the forces within us that interrupt such attempts at self-control. It is, for this reason, deeply concerned with such phenomena as dreams, daydreams, fantasies, and ‘intrusive thoughts’, as well as with actions that escape our conscious intention—our mistakes and mix-ups, our slips of the tongue. It is interested in our tendency to engage in behaviours that, by our own estimation, are destructive and painful—whether in our intimate relationships, our working lives, or our daily habits.

Unlike many approaches to human suffering today, psychoanalysis does not primarily aim at the removal of symptoms. Indeed, a psychoanalytic approach does not presume to understand particular symptoms from the word go (on the basis, for example, of supposedly objective expert or scientific knowledge). Instead, it considers symptoms to be meaningful—indeed, it views them as forms of speech, asking to be heard. Analysis approaches symptoms with openness and curiosity, seeking to discover their significance within the life of the individual sufferer. Analysis does not, that is to say, simply attempt to restore us to a lost state prior to our current difficulties; it seeks to explore, instead, what led to these difficulties, and to help us free ourselves us up for a different future.

As the foregoing perhaps suggests, psychoanalysis is far from a paint-by-numbers approach. Each attempt at analytic work is unique, focused with singular precision on the speech, the challenges, and the history of the person who undertakes it. Its aims are equally singular: analysis does not aim to make us ‘normal’ or well-adjusted, as many contemporary forms of medical and therapeutic intervention do; it does not seek to make us ‘fit in’ or conform to social expectations. On the contrary, it strives to help us interrogate our history of necessary and unnecessary compromises, and to come to grips with the pain and frustration these have caused us. It responds to our suffering not with prepackaged solutions to supposedly generic problems, but by opening spaces for a creative renewal of our experience.

Who is Jacques Lacan?

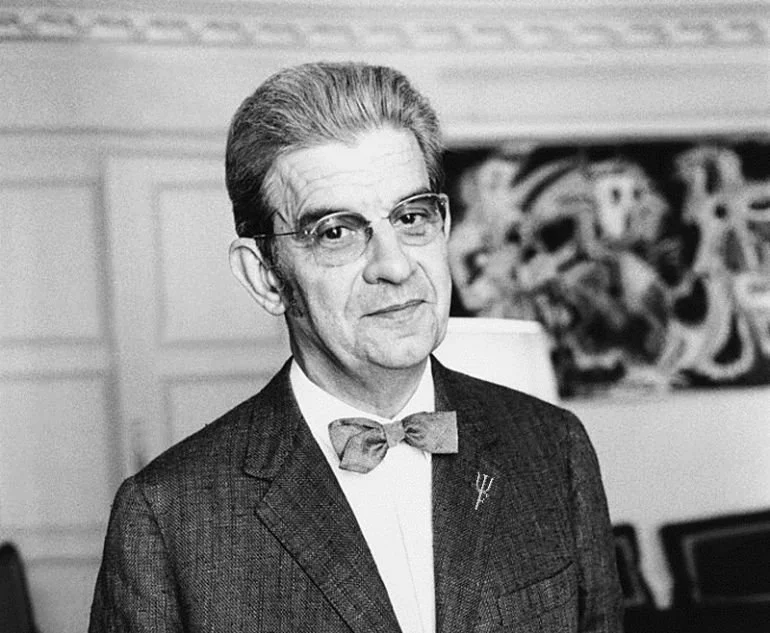

Freud’s pioneering insights—published in books like The Interpretation of Dreams (1900), The Psychopathology of Everyday Life (1901), and Civilisation and its Discontents (1930), as well as in his many famous case studies—have inspired generations of practitioners and theorists. Among these, the French analyst Jacques Lacan (1901-1981) proved one of the most original.

Lacan’s work as a clinician, theorist, and teacher—handed down to us primarily in transcripts of his seminars and in his other writings—was determinedly challenging, both in form and content. Indeed, it has earned him a reputation as one of the twentieth century’s more eccentric and obscure thinkers. Yet Lacan’s influence has grown steadily in many places throughout the world over the past decades, thanks to its powerful and clinically useful insights.

In particular, Lacan emphasises the central importance of language in human life, reflecting on both the way we enter into language and the complex role it plays in our lives thereafter. Language, for Lacan, is not merely a tool we use to convey our thoughts; instead, language shapes our thought and experience, touching us at the deepest levels. It speaks us even as we speak it, making us other to ourselves, and many of our difficulties in life stem from how we deal with this basic fact. With this in mind, a Lacanian approach involves listening carefully for the particularities and peculiarities of our speech, as well as its revealing ambiguities—that is, for moments when we say more than we intend.

Lacan’s work, like Freud’s, has now been submitted to several generations of discussion and development, and its lessons continue to be refined and debated. Indeed, there is arguably no one ‘Lacanian’ approach to psychoanalytic work. However, what many Lacanians share is a critical perspective on many core assumptions and techniques of mainstream psychology, therapy, and even psychoanalysis.

One of the most important of these assumptions is that a clinician can know in advance what would be ‘good’ for an analysand. A Lacanian approach does not involve imposing established norms of thought or behaviour, nor encouraging the analysand to strive after one cultural ideal or another, nor helping the analysand to become more ‘rational’ or in better touch with external ‘reality’. In Lacanian work, we focus instead on articulating the reality of each person’s desire. Another mainstream assumption of which Lacanians tend to be critical is that our difficulties or symptoms are best dealt with by coming to understand them, with a view to establishing a greater degree of control over ourselves. In Lacanian work, we do not strive primarily for understanding, but instead for transformation.